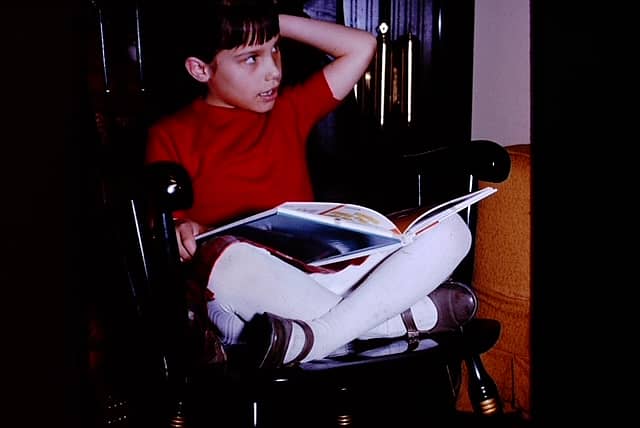

I’ve always loved stories, especially biographies and memoirs. In elementary and middle school, I always seemed to have my nose in a book about a famous person. It wasn’t unusual for me to be called out by a teacher for reading a paperback (paper covers are easier to hide!) inside my desk while she conducted a lesson. It wasn’t that I was bored, it was just more interesting to step away from the task at hand, immerse myself in someone else’s life, and fantasize what it would be like to live that person’s life. The books written by Laura Ingalls Wilder were some of my favorites as were biographies of Helen Keller, Abraham Lincoln, Jane Addams, and Mozart.

By the time I got to high school, I was reading far fewer stories but spinning more plates . . . tending to my musical interests (piano, violin, voice), chasing (or being chased by) boys, and showing up and doing the work for classes (all not necessarily in that order). I did well academically but certainly wasn’t what one might call a “budding intellectual” . . . I just went through the motions and completed the assignments but wasn’t really inspired or even inclined to delve deeper. What I didn’t realize was that earning grades and learning are two different things.

Even in college I remained on auto pilot; college was a means to an end, just the next step in this trajectory called “life.” Early on I did know I’d major in history; it was the best way to nurture my love of non-fiction “stories.” Back in the 1970s, college majors were largely taught in silos; for example, in a European history course it would be unusual to look at how the political movements in late 18th /early 19th century Europe influenced and were influenced by what was going on at the time in literature, the sciences, music, and the arts. The concept of “interdisciplinary” learning, so prevalent in today’s educational world, was new and in its infancy in college curriculum development.

In my junior year, I attended a journalism career seminar that, in a good way, was like getting hit hard on the head with a 2×4. It seems so simple now, but the lecturer used words like “context” and “connections” and “understanding” in emphasizing how one couldn’t possibly write about human rights in the Soviet Union without knowing something of (and appreciating) the history, politics, culture, ethics, psychology, and economics of Russia and its “allies” behind the Iron Curtain (it was a very appropriate example for the time). It could’ve been that I was finally ready to be “educated,” but it was also an “Aha” moment, one of those proverbial light bulb experiences. It all began to make sense.

Since then, catching up has been my M.O. I left college a reasonable writer with a decent foundation in American history and having learned to play a Beethoven sonata on the forte piano. What I lacked, however, was how to critically discern information, a skill that today is seamlessly integrated into most high school and college liberal arts curricula. As it should be, particularly given the interrelatedness and complexity of our world. Two graduate degrees have certainly helped me hone these skills . . . I’m a completely different student and, hopefully, thinker and human being than I was earlier.

To me, education is not just about a knowledge base or looking at a theme, idea, issue, or trend from multiple points of view. Nor is it just about depth vs. breadth. It’s all of these for sure. But at its fundamental level, an education is about making connections through stories – between the past and the present, the present and the present, and the present and the future. And asking, “How?” and “Why?” It’s what I try to bring to my work with students in their college application process . . . helping them, through their writing, tell one of their stories and the connection it might have to something beyond themselves.

Stories – both fiction and non-fiction – certainly make learning more interesting, engaging. They help us to better understand and relate to one another. At their best, stories instill more empathy, a quality with unlimited capacity. And since I believe that education also involves developing a deeper understanding of our common humanity, it stands to reason that education can, and should, be a life-long pursuit. I can’t imagine my life without stories.