As I was thinking about how I might contribute to my colleagues’ wonderful reflections about our annual theme What being a fish means to me, a childhood memory accompanied by one of my dad’s favorite admonitions kept popping into my head. Dad called this constant stream of parental warnings “healthy fear.” I later realized that striking fear into my heart about the countless possible dire eventualities that could befall me was driven by his generation’s view that parenting was foremost about keeping my brothers and me alive!

Of course, drowning was one of those things I was to avoid. Growing up in Maine always in proximity to and enjoying its seacoast and endless lakes, my parents made it clear to my brothers and me that it was important to be a strong swimmer … or else. At a certain point, it was no longer their job to protect us from the beautiful but potentially dangerous water. It was a sink-or-swim, or teach a man to fish, kind of parenting philosophy, if you get my drift ….! Learn to swim … or end up at the bottom of the ocean with the fish. So of course it logically follows that one day I found myself quite literally fending for myself in the deep end.

I was definitely in early elementary school. From what I understand, my mother thought she had found free swim lessons being offered at the local high school pool. For a family of very modest means, anything free was super important. I remember the smell of chlorine, the splashing from constant motion in the water, and the loud echoes bouncing off the cylindrical ceiling as my mom found her way toward an adult at the side of the pool, all the while holding my wrist, ensuring that her shy, hesitant daughter was right behind her. Before I knew it, her firm grasp melted and I was in the deep end, having sliced through the choppy water in the outer lane. I immediately reached for and held fast to the side, trying to stay out of the way of a line of swimmers doing weird somersaults to reverse direction and make their way back to the other end in perfect formation. It took me some time to realize I was by far the youngest kid in the pool. After all, I couldn’t see the submerged faces of the swimmers. I’m not sure when I figured out this was a competitive swim team in the midst of a training, not the swimming lessons my mom had told me about. When I finally looked up from the corner of the pool where I was working hard to be invisible and fully aware that some terrible mistake had been made, my mom was nowhere to be seen. I was in the deep end left to fend for myself.

It took me a long time to become a fish in the school of these other, faster, bigger fish. I had thought I already knew how to swim. But my [healthy] fear from that deep end quickly locked in on how slow and weak I was and how terrible my technique was relative to my fellow fish. And the coaches didn’t seem to much care. I had a lot of tearful days. When it got too physically and emotionally challenging (and it often did!), I would make every excuse you could imagine to get out of the pool, for my mom to come get me from work, or even just to skip a set of intervals. Nothing worked. I had no choice but to keep swimming. So I swam.

I stayed in that outer lane all summer, learning better technique and slowly getting strong and fast enough to swim in tandem with the other fish in my lane. My parents weren’t looking for an “extracurricular activity” for me when they set out to find some free swim lessons to make sure I wouldn’t one day drown. That wasn’t a “thing” back then, at least not for my family. I did join the swim team and I ended up swimming competitively through college and even into adulthood, but that really isn’t the point. The point is that I had no choice but to fend for myself in the deep end.

Twentieth century’s Lev Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of learning and development included the construct he called the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which, simply put, is the space in which we learn and grow — the space between what a learner can do with and without assistance. It’s the space where we learn to swim from the deep end. It’s the space where I really, really struggled to become a fish in a school of fish, the space where people made sure I didn’t drown but left the rest up to me. Left in the deep end, I adapted to the challenge and kept struggling until I developed the emotional and physical skills needed to close that gap in the Zone of Proximal Development and become proficient both at that particular task and its other related skill areas. No one could have done that for me.

A couple centuries earlier, French philosopher Jean-Jacque Rousseau wrote Emile to illustrate the importance of struggle and even pain in the child’s development of the robust skills necessary to navigate the demands of life. In fact, Rousseau was a big fan of pain, writing that it was a child’s “first and most useful lesson.” But he didn’t think of this pain as gratuitous; it was a necessary part of the deliberate, organismic design of human development that created children “small and weak” so that they could learn through natural means, unfiltered by well-meaning, “foolish and pedantic” adults. Rousseau didn’t mince his words about how even loving adults can mess up kids’ development (he sounds less mean in his native French!). But when children learn directly through these struggles unobstructed by well-meaning adults, Rousseau saw “their strength increase,” their “need for tears” decrease, and their ability to “do more for themselves” solidify. Like learning how to swim from the deep end, right? Ah, the making of an adult!

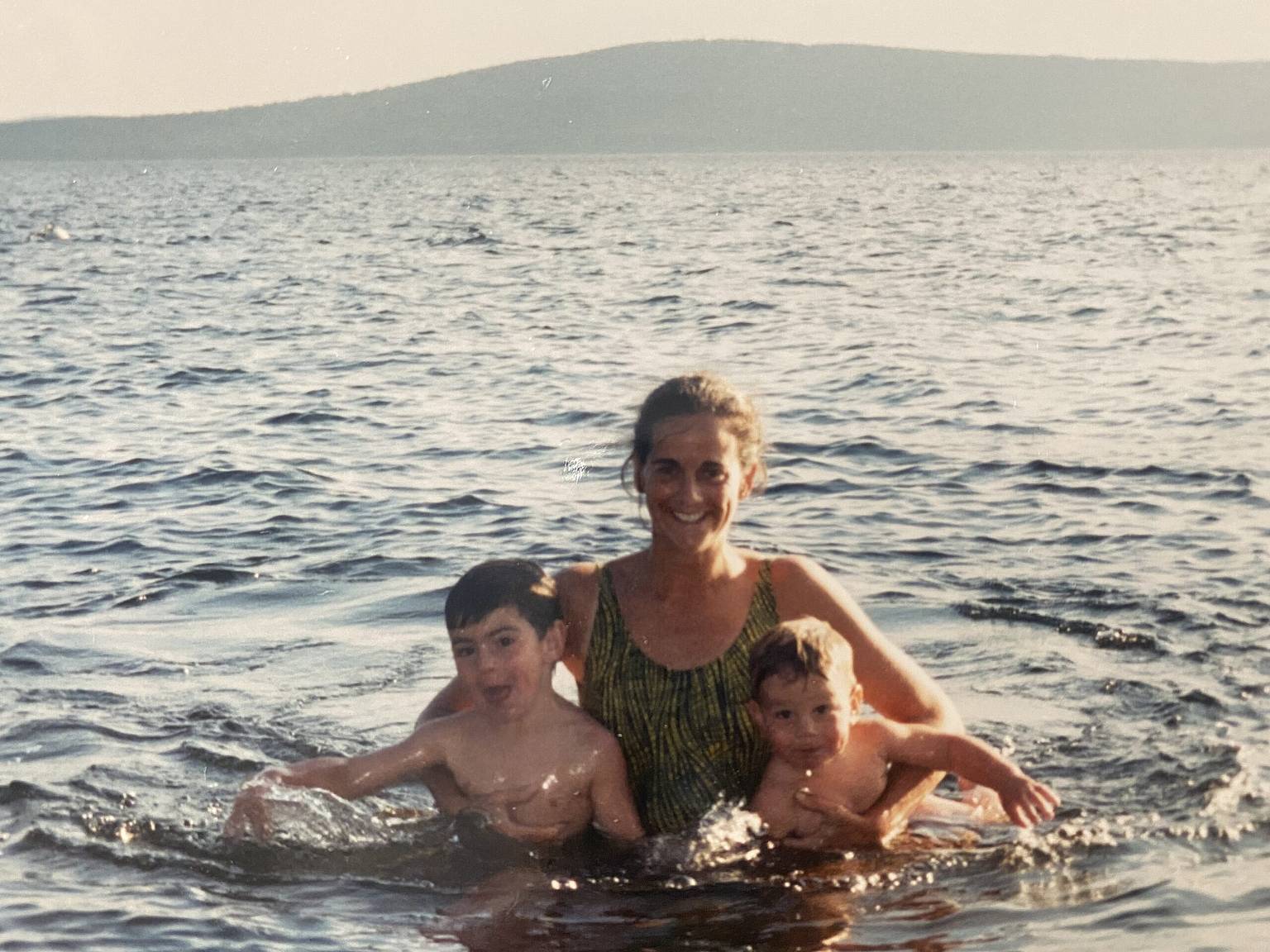

No doubt that throwing your kid into the deep end is at odds with the current “intensive parenting” norms of our society. I certainly promised myself that I would never be as emotionally cold to my children’s suffering as my mom apparently was to mine that day she left me in the deep end. Yep, as the parent of now adult sons, I was that well-meaning parent Rousseau referred to who jumped into the deep end with my kids to “help” them. I’m sure my mom never read Rousseau or Vygotsky, but she clearly didn’t need to! While I have two pretty amazing kids, I will tell you that they are so despite my attempts to correct the apparent failings of my parents’ generation of parenting. My sons figured out how to develop most of the requisite skills to live well in this relentless world even though I too often got in the way of allowing them the full experience necessary to do so. Thank God! At this point I can look back and acknowledge that I obstructed that experience out of my own need to “help” them. It goes without saying that the fact that they are pretty pathetic swimmers is on me!