When tried and true rules of promoting healthy child and adolescent development no longer seem to apply, revisiting the past is not such a bad idea after all

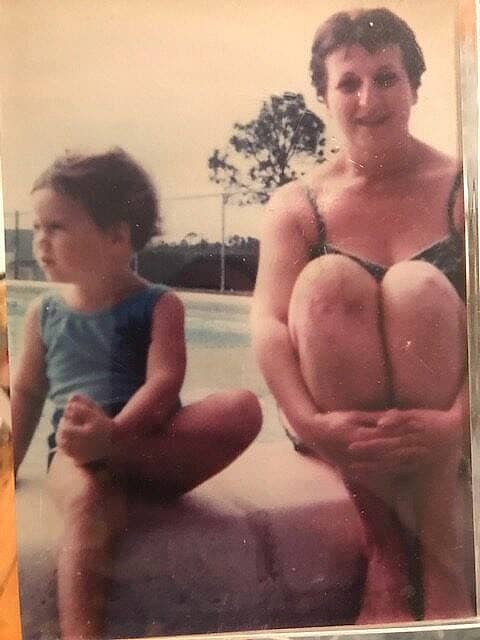

As I’ve gotten older, it’s been hard not to sound like my amazing grandmother Isabelle who reminisced about the enormous challenges she faced as a young person with a strange reverence I didn’t understand at the time. Like any grandchild listening to her elders’ life lessons, I did my fair share of eye rolling. But I also was awestruck by her strength and transcendent accomplishments in the face of the formidable obstacles of her time and of her particular station in it. Of course I took comfort in the fact that I wouldn’t have to live through those challenges of a past that wasn’t mine, that my youth was already easier and that my life ahead would surely be better than hers had been. Hers was a cross I wouldn’t have to bear.

My youthful logic would gradually give way to the reality that, regardless of the unique generational challenges we face, we are bound together by struggle. Maybe that’s why I have started to think like my grandmother about my own youth, despite swearing I would never become that old(er) person, that Boomer. Yes, while not glorifying the past generally or the particulars of my own youth, I have begun to grasp its value in our shared quest to understand and address the challenges of today’s children, adolescents, and young adults who show up in my office every day looking for answers to their epidemic levels of distress, despair, and dysfunction.

I want to be clear that I am not nostalgic by nature (just ask my poor family!). There’s nothing about my past itself that appeals to the pragmatist in me, who favors data over sentiment in searching for a corrective to our youth’s problems. My reflections on my past have occurred as a result of my seeing their intersection with the data that increasingly support the now universal acknowledgment that technology, or screentime abuse, is much to blame for derailing the healthy development of our young people.

Those challenges didn’t exist in my grandmother’s youth or in mine and even my adult, millennial children escaped the brunt of their developmental implications, thank God. I’m old enough that my dissertation study only predicted the impact of technology on one of human development’s primary, critical, requisite tasks related to establishing the foundations of a well-adjusted adulthood: diminishing child and adolescent egocentrism. I count as one of my most cherished privileges the opportunity I have to travel all over the country visiting the world’s (no hyperbole) gold standard therapeutic programs, where the topic of conversation with incredibly talented clinical and educational staff now ALWAYS finds its way to the evils of technology and its influence both on the onset of our youth’s struggles and the therapeutic and programmatic modalities that must evolve to effectively treat them. We typically leave those conversations by swapping book titles. Not surprisingly, I find my current book swaps focused almost singularly on how technology abuse disconnects youth, distorts their thinking and makes them sick.

Not a day goes by that I am not deeply grateful for these great clinicians and their highly effective, premium treatment options. I’m doubly appreciative of their work at this historical inflection point because I have acquiesced to the reality that, as a society, we prefer the role of ombudsman to problem solver and we like to treat diseases more than prevent them. This cultural behavior has only enhanced of late our dependence on these pretty dramatic (and incredibly costly) interventions to get our youth healthy again. In our office, we are finding that kids are suffering so much more and are so much less equipped to manage everyday life that we are having to refer parents to these more dramatic options far more often than just a couple of years ago.

As a developmental psychologist, I wish our focus to be on prevention by capturing the organic power of human development that’s intrinsically mapped in our species to promote healthy growth across domains, while having the added effect of better immunizing against the rampant despair diseases that plague our youth. So I am getting ready to expand on my “Boomerism,” convinced now that it holds some common sense solutions, critically grounded in the science of human development, that have the power to disrupt the onset, severity, and duration of so much of what ails what should be our otherwise healthy kids.

As I shift into a series of blogs on the what-to-do and why to combat the growing and tenacious epidemic of despair diseases, I’m asking you not to confuse me for a luddite. I am not a big blamer or hater, I truly appreciate the contributions technology has made to better our lives, and we must prepare our children to live in a technology-connected world rather than opt-out. And I am fond of saying to all of the parents who come to us looking for answers that “there’s no one thing” that informs our children’s struggles — because it’s true. But this one is a big one!

Here are the upcoming practices and behaviors I will be expanding upon to help elevate the conversation from nostalgia and moral judgment to some good-old valid science:

- Spend time in the natural world. Bump up against its boundaries, feel its permanence.

- Spend time with others in-person. Play team sports. Figure out where you begin and end.

- Learn how to be bored. Low arousal isn’t to be confused with depressed mood and instant gratification doesn’t stimulate healthy development.

- Read. Not just because it makes you more cultured but because it makes your neuro-cognitive capacity grow toward actualized, functional potential.

- Avoid … avoidance. Sit with uncomfortable feelings … rather than “swiping off” what doesn’t feel good.

When recently in California on one of my many road trips to the premier treatment programs across the country, I saw a public service ad that gave an uplifting, albeit fluffy, soundbite asking parents to limit screen time. I thought to myself, that’s a start to turning this conversation into a set of positive value actions, that there are too few of these public service messages, and that they need to be delivered as stronger deterrents. These problems are indeed, as I anticipated, not my grandmother’s problems. But they are our cross to bear because they are weighty and the stakes are so high and increasing daily. Time for all of us to step up and exhibit that strength I saw in my grandmother so long ago. If you made it this far, thanks for joining in the battle and back to you soon!